Int'l Trade Policy: A look at GATT, the WTO and Lighthizer's Perspective

Free post. Heavily influenced by Robert Lighthizer's No Trade is Free

Today’s post is free to the public. Thank you for subscribing. Occasional forwarding is okay. If you are not a member, please sign up here.

It is important to remember that no country became great by consuming. They became great by producing. - Robert Lighthizer

International trade agreements shape America’s economy, industries, and workforce. Yet, their complexities often keep them out of public discussion. This post provides an overview of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its successor, the World Trade Organization (WTO), with key insights from No Trade is Free by Robert Lighthizer.

GATT: The foundation of the modern trade system

Established in April 1947, GATT was signed by 23 nations to create a multilateral framework for global trade. Over time, it evolved into a system that facilitated trade negotiations while allowing nations to safeguard domestic interests.

“[GATT] spawned a bureaucracy-laden organization in Geneva, Switzerland, to facilitate the negotiation of international trade deals.” (No Trade is Free, p. 49)

Critical provisions:

Most Favored Nation (MFN): Each member had to extend any trade liberalization granted to one country to all members, with limited exceptions (e.g., free trade zones and special treatment for developing nations).

Negotiated Tariff Schedules: Members agreed to cap tariffs at negotiated levels.

National Treatment: Imported goods had to be treated no less favorably than domestically produced “like” goods once inside a country.

Importantly, GATT did not create a system of unregulated “free trade.”

“The GATT did not introduce an era of unregulated trade. Instead, US policymakers regularly used their constitutional authority to ensure that efforts to lower tariffs and encourage trade with US allies would not disrupt the US economy and hurt American workers.” (No Trade is Free, p. 50)

GATT’s trade liberalization efforts were gradual and negotiated over decades, primarily benefiting U.S. allies. When trade deficits threatened U.S. economic interests, leaders took action:

President Nixon intervened to address trade imbalances.

Congress enacted tools to shield U.S. industries, such as Section 232 (national security tariffs), Section 301 (retaliatory tariffs), and stronger anti-dumping/subsidy laws (No Trade is Free, p. 51).

Eventually, GATT transformed into the WTO in 1994—with consequences that Lighthizer argues were disastrous for U.S. manufacturing workers.

The WTO: A shift in global trade rules

…with awful results for manufacturing workers.

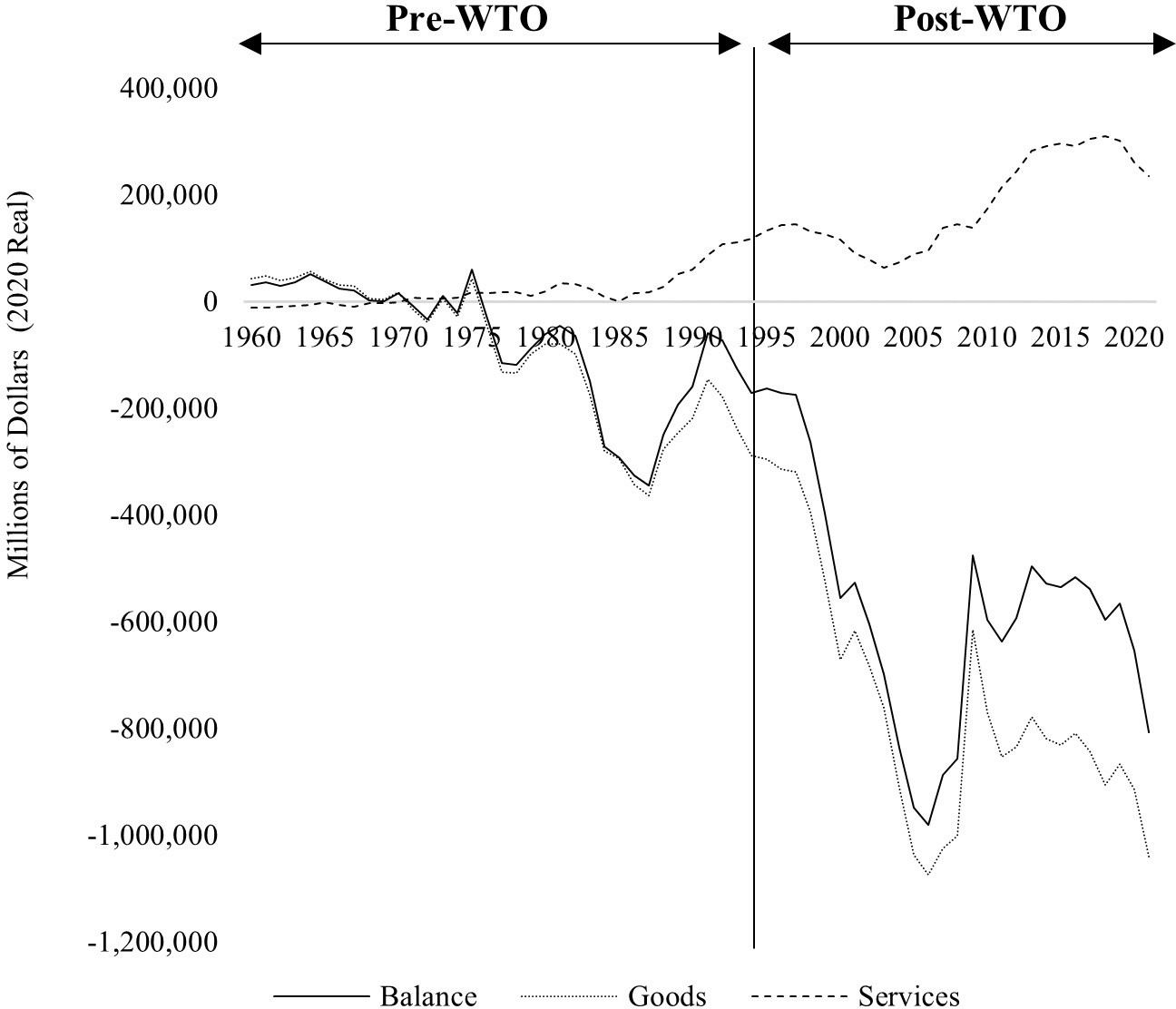

United States Trade Balance: Total, Goods, Services (Millions of 2020 Dollars)

The WTO expanded GATT’s framework, introducing new disciplines that extended beyond goods into services, intellectual property, agriculture, and textiles—areas previously outside multilateral trade rules.

Key Changes Introduced by the WTO:

“Single Undertaking” Rule: Unlike GATT, where some agreements were optional, WTO membership required nations to adopt all trade agreements, creating a system with over 60 binding agreements from the Uruguay Round.

Development Focus: The WTO placed more emphasis on development, granting special treatment to developing countries, including longer implementation periods and lesser obligations.

However, the most significant changes were institutional:

1. WTO as a Permanent Institution

Unlike GATT, which was signed as a temporary arrangement1, the WTO was established as a full-fledged international organization with:

A legal personality, allowing it to enter agreements and function as an entity.

A Secretariat in Geneva to oversee trade negotiations and compliance.

Defined decision-making procedures under a Ministerial Conference and General Council.

Diagram of the WTO’s organizational structure

2. The WTO Dispute Settlement Mechanism (DSM): A Powerful Enforcement Tool

The WTO introduced a binding dispute settlement mechanism, a major departure from GATT’s weaker enforcement system.

Under GATT: Any ruling required consensus—including from the losing party—allowing countries to block unfavorable rulings.

Under the WTO: The “reverse consensus” rule meant that dispute rulings were automatically adopted unless every member (including the winner) agreed to reject them.

The system also introduced a two-tier structure:

Dispute Panels: A panel of experts reviewed trade disputes and issued rulings.

Appellate Body (AB): Countries could appeal legal interpretations, and the AB’s decision became binding.

Initially, this mechanism worked as intended, with most countries complying. However, over time, the Appellate Body became a major source of controversy.

The WTO’s Dispute System: A Breakdown in Functionality

Lighthizer and other critics argue that the Appellate Body (AB) evolved beyond its original purpose, engaging in judicial overreach by:

Creating new trade rules instead of strictly interpreting agreements. (“Became an unelected lawmaking body, creating rules that have vast implications for international trade.” – No Trade is Free, p. 69)

Issuing “findings of fact” despite WTO rules precluding them from doing so.

Ignoring procedural deadlines, often exceeding the 90-day limit for rulings.

Extending judge terms beyond limits, allowing expired members to rule on cases.

Financial incentives to extend cases, as AB judges were paid daily.

Perceived bias against the U.S., ruling against U.S. policies on taxation, subsidies, and regulatory standards.

Consequences and the U.S. Response:

By the 2010s, tensions escalated, with the U.S. arguing that the AB had become a self-perpetuating judiciary that weakened U.S. sovereignty. In response, the U.S. blocked new AB appointments, and by 2019, the AB ceased functioning, paralyzing the WTO’s dispute resolution system.

Lighthizer’s Critique of the WTO: A System that Restrains U.S. Sovereignty

Lighthizer argues that the WTO locks the U.S. into outdated commitments, preventing adjustments for changing economic conditions:

Bound Tariff Rates: Members cannot unilaterally raise bound tariffs, even when global conditions shift.

Different Legal Traditions: The Anglosphere views trade agreements as rigid contracts with precisely written obligations, while Europe sees them as evolving, allowing reinterpretation to enable favorable outcomes. This difference enabled looser interpretations of WTO rules over time.

The Appellate Body’s overreach was particularly problematic, as WTO rulings began interfering in domestic U.S. policy2, including:

Taxation: Ruling against U.S. corporate tax structures.

Subsidies: Striking down U.S. measures to assist industries harmed by unfair trade.

Social Policy: Overturning U.S. gambling restrictions.

It became clear to Lighthizer and others the Appellate Body was biased against the United States3.

Lighthizer’s Proposals to Fix the WTO

Lighthizer argues that the WTO, in its current form, is outdated and unfit for modern trade realities. His solutions:

Reset the global tariff system to allow flexibility.

End the “FTA end run” around MFN treatment, preventing abuse of free trade agreements.

Limit “developing country” status to only the poorest nations (e.g., preventing China from claiming special treatment).

Counter Chinese economic aggression by permitting compensatory tariffs and unilateral action against predatory policies.

Introduce a “sunset clause” for WTO agreements to ensure periodic renegotiation where the agreement expires when met with negotiation deadlock.

Mechanism to assure long-term balanced trade to prevent chronic trade imbalances.

Scrap the current dispute settlement system, model a new one after commercial arbitration.

Conclusion: A WTO in Crisis

The WTO was created to enforce trade rules and provide stability, but over time, it has drifted from its original intent. Lighthizer’s critique highlights how the system now limits U.S. sovereignty, prevents tariff flexibility, and has an activist dispute mechanism that undermines national policies.

With the Appellate Body now defunct and trade tensions rising, the future of the WTO remains uncertain. Whether it will be reformed, replaced, or abandoned is an open question—but what is clear is that trade policy is no longer a niche topic. It directly impacts jobs, industries, and national sovereignty, and it deserves a greater public debate.

Whether consuming or engaging in this public debate, please remember that free trade is a nice theory that “works” in abstract vacuum, but it doesn’t exist in practice. Reject the unregulated free trade ideologues. More to come on this in a future post.

Where trade is concerned, most Americans want the same thing: balanced outcomes that keep trade flows strong while ensuring that working people have access to steady, well-paying jobs. Neither old-school protectionism nor unbridled globalism will achieve that. Instead, as the United States confronts future trade challenges, it should chart a sensible middle course—one that, at long last, prizes the dignity of work and affirms a shared vision of the common good. Such visions are not self-executing. They require concerted and often aggressive courses of action. — Robert Lighthizer

If you read this far, thank you—we clearly have a shared interest. Please consider hitting the like button, it helps others discover us, or consider subscribing to a paid tier to support my work. Comments are only open to premium members, but feel free to DM me with any thoughts.

The original plan was to create a much broader International Trade Organization (ITO) under the framework of the United Nations. The ITO was supposed to handle not just trade but also investment, competition policy, employment, and international business conduct. However, the U.S. Congress refused to ratify the ITO Charter, and by 1950, the effort to establish the ITO collapsed.

“90% of the disputes pursued against the United States have led to a report finding that the US law or other measure was inconsistent with WTO agreements. This means that on average, over the past 25 years, the WTO has found a US law or measure WTO-inconsistent between five to six times a year, every year.” Page 68, No Trade is Free

“Tom [Graham] is a friend of mine and was for several years my partner at our law firm. Privately he told me that the Appellate Body is clearly biased against the United States in his experience [he was on AB from 2011 to 2019] and that whatever I think the size of the problem is, it is actually larger.” Page 73, No Trade is Free