Industrial Commons

A country does not rise to the level of its innovation. It falls to the level of its industrial commons.

My industrial policy bender has begun, consider yourself warned. Half of this post is available to the free-tier. Occasional forwarding is okay. If you are not a member, please sign up here.

A country does not rise to the level of its innovation. It falls to the level of its industrial commons.

Industrial Commons

I came across this term after I published Industrial Policy, A Foundation. It’s the perfect term for what I was calling “Scaling Value” in that post.

The industrial commons is what enables scaling. It consists of two key components:

The ecosystem – suppliers, logistics, infrastructure, capital access, and more.

Technical knowledge – process know-how, workforce expertise, and accumulated experience within the industry.

Despite the word industrial, this concept isn’t limited to manufacturing. For example, Silicon Valley was once a hardware industrial commons focused on silicon and semiconductors; today, it’s a software/digital industrial commons.

Fragility and Importance

Industrial commons are like good reputations—built over time, yet easily destroyed. If one critical link in the chain disappears (a supplier, skilled labor force, or piece of infrastructure), the entire ecosystem weakens significantly.

Why does this matter? In today’s world, many goods and services require economies of scale to compete globally. Without scale, companies lose market share. That decline can start a downward spiral:

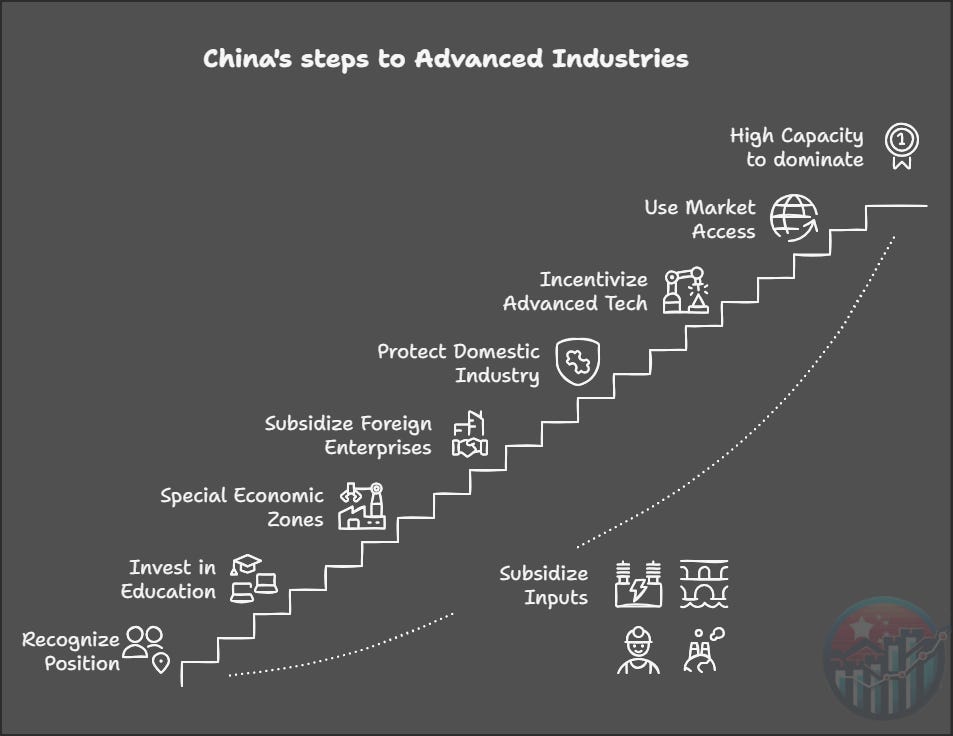

China’s Playbook: Building an Industrial Commons

China has executed a textbook example of industrial commons development. Some of its key policy tools included:

Special Economic Zones (SEZs) – to attract foreign investment and build clusters of expertise.

State infrastructure investment – to ensure logistics, ports, and supply chains were world-class.

Taking low-margin industries – electronics, chemicals, and materials were seen as stepping stones, not dead ends.

Subsidies, market access, and trade barriers – to protect and nurture domestic industries.

See China’s epic progress in the following chart from Robert Atkinson (ITIF).1

China’s industrial commons strategy was simple (to explain):

Recognize their starting position – huge population, high poverty, low resource wealth.

Invest aggressively in industry and capacity – knowing that scale leads to dominance.

Achieve market share dominance – then move up the value chain.

Why Build Industrial Commons?

Robust industrial commons offer major advantages, including:

1. Process Knowledge: The Unwritten Moat

Scaling production requires deep process knowledge—an asset that isn’t found in textbooks or research papers. Unlike theoretical knowledge, process knowledge accumulates within companies and industries over time as workers refine production techniques, solve problems, and develop efficiencies.

A prime example is Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). Their ability to build high-yielding fabs for advanced semiconductors is process knowledge honed over decades. It’s an enormous barrier to entry. More yield = lower costs = more market share = more profits = more R&D = stronger industrial commons.

2. The Andy Grove Warning: Don’t Abandon “Commodity” Industries

Andy Grove famously warned that losing “commodity” industries can cripple future technological development:

“I disagree [that it’s a success to lose the ‘commodity’ television industry]. Not only did we lose an untold number of jobs, we broke the chain of experience that is so important in technological evolution. As happened with batteries, abandoning today's ‘commodity’ manufacturing can lock you out of tomorrow's emerging industry.” — Andy Grove2

Losing an industrial commons today means losing the ability to scale future innovations tomorrow.

Thought Experiment: Industrial Commons in the Age of AI

Imagine a world where Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI) is attained. ASI rapidly discovers new scientific breakthroughs, running billions of simulations and directing automated labs to conduct real-world experiments.

Who benefits?

Only nations and companies with robust industrial commons will be able to translate these discoveries into physical reality at scale.

For instance, suppose ASI makes radical advances in robotics. The countries with strong robotics industrial commons will be first to implement them in manufacturing, defense, logistics, and healthcare.

It won’t matter where the discoveries are made—what will matter is who has the industrial commons to scale them.

The AI Economy: From Bits to Atoms

As I was finishing this post, I watched J.D. Vance give a speech on AI where he said:

“It’s my view that tech innovation of the last 20 years has often conjured images of smart people staring at computer screens engineering in the world of bits, but the AI economy will primarily depend on, and transform, a world of atoms.

Now at this moment, we face the extraordinary prospect of a new industrial revolution, one on par with the invention of the steam engine or Bessemer steel, but it will never come to pass if overregulation deters innovators from taking the risks necessary to advance the ball, nor will it occur if we allow AI to become dominated by massive players looking to use the tech to censor or control users’ thoughts.”3 [emphasis added]

Hard agree. The past two decades of tech innovation have been dominated by software, where regulation has been relatively light, and capital has flowed freely due to high ROI and lack of NIMBYism. But AI’s biggest impact won’t stay confined to digital spaces—it will reshape the physical world. Scaling AI-driven breakthroughs in robotics, materials, healthcare, energy, and manufacturing will depend on strong industrial commons, and that means rethinking how we regulate and incentivize the industries of the future.

Building industrial commons isn’t just about investment—it requires a hard look at onerous regulations that may be hindering innovations from crossing the valley of death—the gap between breakthrough research and large-scale commercialization. Right-sizing these regulations for the AI-driven industrial era will be critical if we want to lead in the next wave of technological transformation.

High-Stakes Choice: Nurture, Build or Fall Behind

Neglecting the industrial commons isn’t just an economic oversight—it’s a strategic vulnerability. Once lost, rebuilding it is exponentially harder, requiring not just investment but also time, expertise, and a coordinated ecosystem.

However, there is another option for rapidly constructing a micro industrial commons: extreme vertical integration. This approach, though incredibly difficult, involves a company or coalition amassing capital, talent, and resources to aggressively build an ecosystem from the ground up. An historical example is the U.S. industrial mobilization before entering World War II, where firms like Ford, GM, and Boeing rapidly scaled production with government support—a story well-documented in Freedom’s Forge. But extreme vertical integration still requires alignment with policymakers and, in many cases, broader societal backing.

Whether through long-term industrial commons development or rapid vertical integration, the lesson is the same: if we fail to actively nurture our ability to scale, we won’t just lose market share—we’ll lose the capability to lead in the next technological revolution.

In the 1930s, the Empire State Building—the tallest in the world at the time—took 410 days to build. A decade later, the Pentagon took 16 months.49 In the span of eight years during the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration built some 4,000 new schools, 130 new hospitals, 29,000 new bridges, and 150 new airfields; laid 9,000 miles of storm drains and sewer lines; paved or repaired 280,000 miles of roads; and planted 24 million trees.

Compare those feats to more recent ones. In 2022, an opinion piece in The Washington Post observed that it had taken Georgia almost $1 billion and twenty-one years—fourteen of which were spent overcoming “regulatory hurdles”—to deepen a channel in the Savannah River for container ships. No great engineering challenge was involved; the five-foot deepening project “essentially . . . required moving muck.” Meanwhile, raising the roadway on a New Jersey bridge took five years, 20,000 pages of paperwork, and 47 permits from 19 agencies—even though the project used existing foundations. [emphasis added] — Over Ruled: the human toll of too much law, by Neil Gorsuch

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to a paid tier to support our work. Today’s graphics were generated by Napkin AI.

China Is Rapidly Becoming a Leading Innovator in Advanced Industries, Robert Atkinson. September 16, 2024

Originally mentioned in Industrial Policy, A Foundation, Mr. Grove’s article was originally published by Bloomberg: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2010-07-01/andy-grove-how-america-can-create-jobs

Props to Jonathon Sine, who dug up a PDF of the article here.

Transcript of J.D. Vance’s speech at the Paris AI Summit 2025 from jingjupost.com