Explaining the Tariffs to My Former Chinese Colleague

What tariffs, trade deficits, and the industrial commons have to do with each other—and why China’s model may be running out of road.

This post came out of a conversation with a former colleague of mine in China. They are smart and curious, but like many people, live inside a national information bubble. They don’t follow global trade closely—and definitely don’t track macroeconomic trends or tariff policy. When they asked me what’s going on with the new Trump tariffs, I realized how hard it is to explain this stuff simply. A full explanation could fill a book. This isn’t that.

I’m not claiming these tariffs are the perfect strategy or even a good strategy. I know some of the ideas here are simplified and might invite pushback. That’s fine. My goal is to offer a clear and honest explanation (take?) of how the world trading system ended up so unbalanced… and why that matters.

Thank you for subscribing. Occasional forwarding is okay. If you are not a member, please sign up here.

"Better to start up a thousand wrong roads than to keep going nowhere because you know the way." - Robert Brault

Explaining the Trump Tariffs to My Chinese Colleague

The global trading system is unbalanced 不平衡. This is evident in the persistent trade imbalances. In the theoretical world of “free trade” this shouldn’t happen. Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage assumes everyone benefits. But that theory doesn’t hold up in the real world today. I imagine Ricardo would update his views. Massive-scale manufacturing, built with state subsidies, was never what he had in mind.

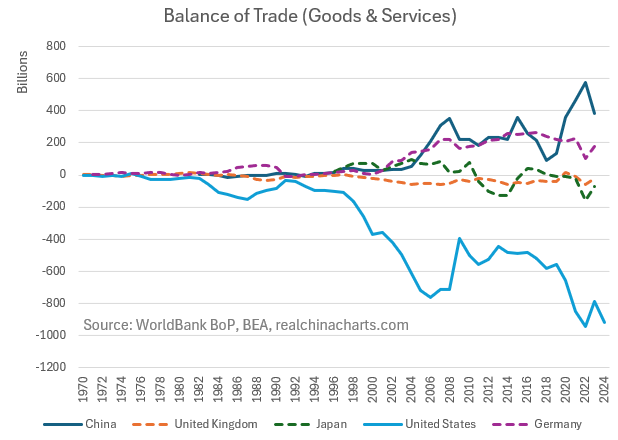

Of the persistent trade imbalances, China has the largest surplus and the U.S. has the largest deficit.

China’s trade surplus, using China customs data.1

And here’s World Bank balance of payment data2, U.S. is the light blue line on the bottom. Negative = deficit.

So what’s causing all this?

There are 2 key angles and they have recently converged.

1. The populist view

A lot has changed since Ricardo’s time. Capital can now move freely across borders. So can technology and raw materials, thanks to digitization and global shipping. But labor is still stuck, just as it was in the 19th century.

The populist view:

Free Trade Agreements made it safer for capital to move abroad and invest in less developed countries. This was great for capital and pretty good for the workers in these countries. But not so great for workers in developed countries.

Dr. John Rutledge explains it well:

Opening trade between countries that had different resource endowments and different relative prices would trigger redeployment of capital, labor, and goods (trade), which would drive the full set of relative prices closer together. That would certainly increase total production for all countries combined. But it would not result in the free trade argument that each nation’s output goes up as a result.

To put names to the story, opening trade between capital-rich America and capital-poor China has induced capital owners to redeploy it from where it is abundant to where it is scarce. The capital owners–today we call then the 1%–are unambiguously better off as a result. Workers in China are better off because they are

not[now] more productive. Workers in the US are now worse off because they have fewer factories and machines for producing product.

The result: industrial commons in the U.S. have eroded and our workers are worse off—opening the doors for populism.

2. China’s barriers

China’s economic structure is set up so that everyday people 老百姓 don’t get much money. Instead, resources are funneled into businesses, especially exporters and factories. For example, labor unions are illegal, and subsidies are aimed at production (producers), not consumption (households). For more on this, see my post Welfare for Whom?

China also follows a strategy of import replacement. In simple terms: “We sell you our stuff, and we do not buy your stuff.” When China must import something, it works to incentivize3 domestic alternatives and eventually replace the foreign version/good.

Some of the other barriers to trade (read imports) that China uses/used are foreign currency exchange management (making the CNY weaker), harsh customs polices4, forced JVs, cheap financing from state banks, market access restrictions, among others.