Charts This Week #9

CNY devaluation: the weakening, the growing up and the reaction, RU-PRC scrutiny, battery supply chains, data quality

*This is a premium members post. A free preview of about 50% is provided. It’s a long one, apologies! Thank you for your support!

CNY devaluation

Making the headlines.1

‘When’, not ‘if’

Russell Napier, a financial historian we highly respect, believes it is not a matter of “if” but “when”.2 He also doesn’t like the term “devalue” and instead likens China’s fixed currency regime to child-like for such a large economy. He thinks China should grow up.

…Falling CPI, falling PPI, falling property prices, credit distress and all of that is what is compatible with something more than a recession, something that looks more like a depression. But then there's one statistic which isn’t in any way compatible with any of that, and that is the reported level of 5% of real growth. But solving this problem is not difficult. There was a man who invented an answer to this in 1933.

His name was Irving Fisher, writing in Econometrica, he came up with a prescription to deal with debt deflation. It’s print money, that’s what it is. And that’s where Xi is going to end up. And that’s why I think it has to move to flexible exchange rate. I don’t use the term China has to devalue, I use the term it has to grow up.

A grown up country has an entirely independent monetary policy with a flexible exchange rate. New Zealand has one. If mighty New Zealand can operate with a flexible exchange rate, I suspect that China can also do so.

He goes on to explain China’s equity markets are signaling, with their valuation roughly at 10 times earnings, is effectively deflation. “Because deflation can wipe out the equity portion quite quickly.”

Assets fall faster than liabilities

Average sales prices fall faster than input prices

Cash flow falls faster than interest payments

China is already lowering interest rates.

We should note, rate differentials (higher in US, lower in China) do put weakening pressure on the CNY.

If you think there is an high likelihood of a major devaluation, one option is to accumulate gold.

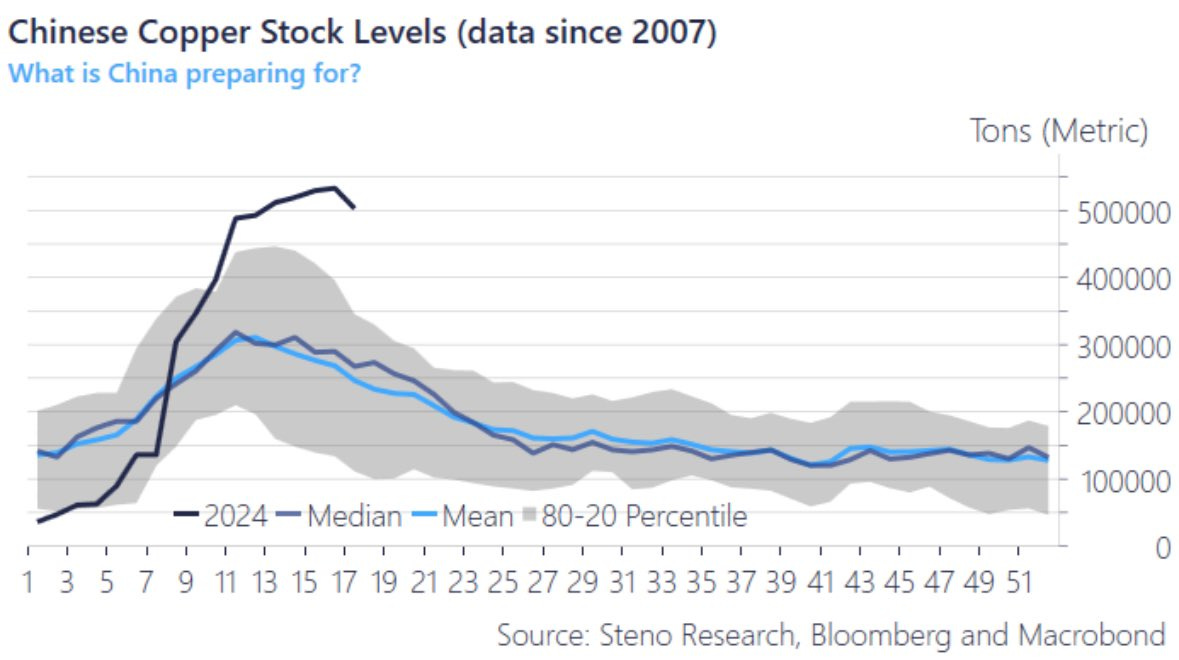

Another option to offset some of those imported input prices (which get more expensive with devaluation) is to stockpile.3

“There are no solutions, only trade offs.” - Thomas Sowell

There are three parts to a devaluation for China:

(1) the weakening,

(2) the “growing up”, and

(3) the (inevitable?) reaction.

The weakening

Chinese officials have stated a policy goal of increasing domestic consumption. Michael Pettis has a good thread on why a devaluation would not help that goal (because it further reduces household share of income).

The way it works:4

Exporters are businesses, households are workers therefore mostly net importers.

Businesses hire workers and pay them in CNY.

Exporters receive foreign currency for their exported goods.

A weaker CNY means

(1) exporter’s operating costs go down relative to their sales price and

(2) they can thus lower prices in their sales currency which allows them to take market share (increase sales volume).

Households are stuck with the same CNY earnings, but now the imports they purchase priced in foreign currency are more expensive.

If you’re in the Chinese government, this doesn’t sound that bad. "支持国产" import replacement type-thinking can still prevail.

There’s another reason govt likes it. It allows production to go up, GDP benefits, jobs remain or increase with the result: officials look good! We’ll skip the part where some officials used to(?) get some offshore, cough, handouts.

This isn’t just Chinese businesses or SOEs, foreign businesses benefit from this too. China has export zones where VAT gets rebated. Businesses can set up in those zones, hire Chinese labor, import the inputs, manufacture the goods and export for even cheaper. Perhaps Williams-Sonoma was buying cheaper products from one of these zones and calling them “Made in USA”.5

Investors benefit too. Business profit margins rise when revenues grow faster than costs. Selling in a strengthening currency and paying in a weakening one helps margins.

Households incrementally benefit a little as there may be additional jobs. But in general, it isn’t helpful for households. They need to purchase more expensive imported goods. The domestic goods that require imports will also be more expensive and/or of lower quality. For example, a friend was recently traveling abroad and found the same black hair dye as they use in China and noticed it was much better than the one in China.

A devaluation simply adds to the existing structural disadvantages for Chinese households: China’s indirect tax structure (VAT), paying for high land sale prices (as apartment buyers), and limits on moving savings (closed capital account), weak social safety net, among others. These disadvantages are evident in the employee share of

For Chinese nonfinancial corporations, employee compensation is only worth about 44% of gross value added, whereas the equivalent measure of the labor share in the U.S., Europe, and Japan is ~60%.6

The “growing up”

China’s currency is fixed by the PBOC, managed against a basket of trading partner currencies. China also has capital controls. China is (c) in the impossible trinity.

China needs an independent monetary policy if it wants to break a debt deflation spiral. Growing up means abandoning the PBOC’s daily fixing of the mid-point exchange rate and allowing the CNY to clear at a rate where capital is willing to enter. This will move them to (b) in the trinity.

Some thoughts/questions on what changing the exchange rate policy means:

Is the switch fast or gradual? We’d bet China picks gradual.

Too gradual may limit development of hedging markets by creating perception of an implicit guarantee (plenty of those already in China).

Will China pick another anchor, BRICS basket, SDRs, gold, oil or choose to target inflation?

Are China’s standing facilities, open market operations and repo activities sufficient?

“Policymakers think that exchange rate stability is what promotes the use of the yuan as an international currency, [Bob Elliott] said. “The problem is that it’s manipulated, not the fact that it’s not stable.”7

Flexible exchange rate could help internationalization of CNY.

Capital controls, does China still need them?

We think the Party wants the “bird cage”8 which limits capital flight as much as possible. But we also think a lot of Chinese people prefer living in China. There are many benefits and great things about living in China. Yes, maybe some capital—maybe a lot of capital—will leave the country, but mostly everyone will stay in China. The capital that leaves will bring back to China returns on investment.

But this is a big change. Currently, the Party can guide China’s development with capital, subsidies and policies to favored industries. Local cadres can boost their scorecards9 by pulling their own guidance levers. Alternatively, if households become much wealthier and are given more flexibility on how their capital is used, perhaps some of the Party’s guidance-power is diminished. Or maybe not, maybe there is a third way, as often there is.