Charts This Week #8

LGFVs, Q1 data dump, household debt & energy security

*This is a premium members post. A free preview of about 50% is provided. Thank you for your support!

LGFVs

Jon Sine, who writes Cogitations.co, released his extremely thorough piece on LGFVs, The Rise and Fall of LGFVs. It’s a long, extremely well researched piece (99 footnotes!) with plenty of great charts, many of which are hidden in the footnotes(!). The whole piece is worthy of your time.

Here we share some excerpts and charts..

The LGFV, as we will see below, rather arose as an indirect result of three conjoined and systemic issues: fiscal centralization and decentralized local developmentalism, the Party-state’s organizational and incentive system, and the weakly institutionalized nature of China’s political system.

Trying to get a handle on the size of LGFV debt is difficult. The last official bottoms-up look at LGFV debt was an audit conducted in 2013, over a decade ago! But there is some data. Overall, there are about 12,000 LGFV entities (according to CBIRC 2021). About 3,000 LGFVs have accessed the bond market and are required to disclose financials. So about 25% coverage, a decent sample size.

LGFV Chart 1: IMF’s estimates of LGFV debt as a percent of GDP (2023)

The above chart from the IMF is from their 2023 Article IV for China, which is done annually and it constantly revises up the proportion of LGFV debts in China’s economy.

LGFV interest-bearing debt is even larger than the IMF data above suggests. An unavoidable limitation of assessing LGFVs via bottom up data, as all of the above sources do, is that it only captures the 2-3,000 LGFVs that have issued bonds and published associated financials. Another 9-10,000 smaller LGFVs have never accessed the bond market and are therefore simply missing from the data.

Mr. Sine makes very reasonable estimate (using the pareto rule 80/20) for the total amount of LGFV debt of around 60% of China’s GDP or CNY 75 trillion. A range of the total size could look like CNY 75 to over 100 trillion in 2023.

While the precise size of LGFV debt is difficult to nail down, we can say with confidence that the proportion relative to GDP is very significant, at least 60%.

LGFVs are big, but are they sustainable?

No.

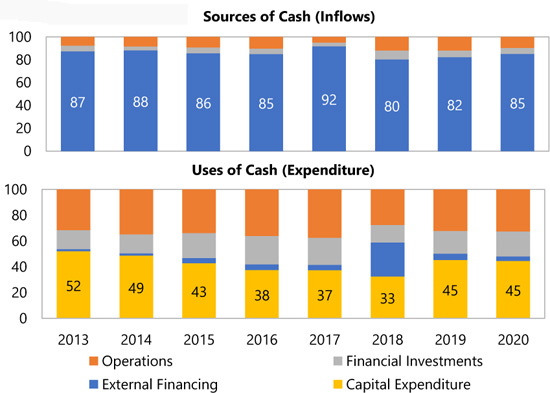

About 85% of LGFV cash inflows come from external financing.

LGFV Chart 2: LGFV Cash Flows (IMF 2022)

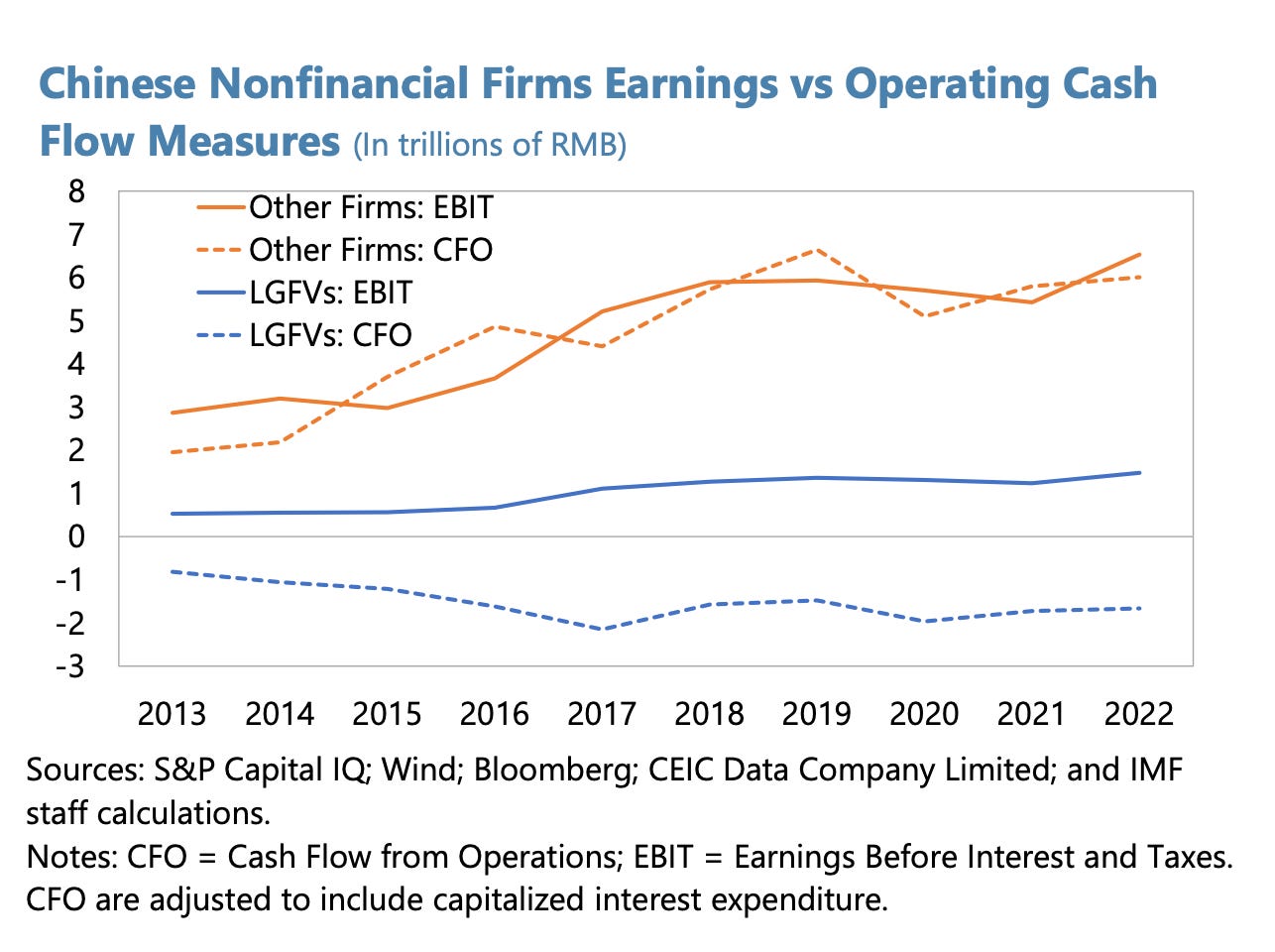

LGFV Chart 3: LGFVs operating cash flows are negative

We learned quite a bit reading the fantastic piece, for example (emphasis ours):

Banks are the cornerstone of China’s financial system and were really the only game in town capable of facilitating a burgeoning land finance system. Most know about the big banks, but the stories slightly more complicated. To get localities on board with the 1994 fiscal overhaul, Zhu Rongji made a “grand bargain” with localities: in exchange for acquiescing to fiscal centralization, localities would get the right to establish their own locally controlled banks.38 As Adam Liu, whose research focuses on this topic, puts it: what is “rarely discussed is the most vital component of Beijing’s compensation package [for the 1994 budget reform]: local governments were offered the privilege of entering the banking sector.”39 When Beijing closed the front door with its budgetary restriction on lending in 1994, it opened a window.40

I’d add, from my prior experience in project financing, these local banks have easier credit requirements.

Here, Mr. Sine had us in stitches (emphasis ours):

No longer simply acquiescing to their use, Beijing began directing local governments to deploy LGFVs for countercyclical infrastructural stimulus and tasked the banking system with funding them.46 The People’s Bank of China explicitly called on local governments to use LGFVs to borrow, the banking regulator (CBRC) explicitly encouraged LGFV use, as did the Ministry of Finance.47 Buyer of narratives therefore beware, lest you fall victim to the woe is me central government fairy tale. This puts a bit of a lie to the notion that Beijing is effectively a responsible parent figure always trying to constrain misbehaving local officials.

Yours truly remembers this time quite fondly. At my local internet (gaming) cafe I met a skilled DotA player, who also worked in a SOE that was given billions of CNY and told to “invest in anything that makes money.” He would often buy all the Chuanr guy’s inventory and share with everyone. Good lad.

“Show me the incentives and I’ll show you the outcome” - C. Munger

As Jon captures well, the story about LGFVs is really about complicated, oft-misaligned incentives in China’s fiscal, financial and economic system. The players are just about every institution, developers, businesses and household in China.

Here we try to explicitly lay out some of those parties and their incentives.

Central govt.

Ministry of Finance has been trying to limit LGFV debt growth because of risks to financial stability (they don’t want a financial crisis).

At same time, central govt has, on occasions, promoted utilization of LGFV financing channel for counter-cyclical purposes.

Local govts.

Have incentives to increase LGFV debts: they’re on the hook for public expenditures, their officials are ranked on short-term GDP growth, they want to attract job providing businesses to their area.

Easiest channel for infrastructure financing.

Property developers.

Profits. Huge profits. Here are Country Garden and Vanke’s profits since 2005 in CNY.

Households.

With bank deposit savings rates suppressed, households seek higher yielding options. This brings them to Wealth Management Products, Insurance Products, Trust Products, etc. that offer higher yields. AKA the non-bank shadow lending market.